Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms

An aortic aneurysm is a bulging, dilation, or ballooning in the wall of a blood vessel, usually an artery, that is due to weakness or degeneration that develops in a portion of the artery wall. Just like a balloon, the aneurysm enlarges, stretching the walls of the artery thinner, thereby compromising the artery wall's ability to stretch any further. At this point, the aneurysm is at risk of rupturing and causing potentially fatal bleeding, just as a balloon will pop when blown up too much.

An aortic aneurysm is a bulging, dilation, or ballooning in the wall of a blood vessel, usually an artery, that is due to weakness or degeneration that develops in a portion of the artery wall. Just like a balloon, the aneurysm enlarges, stretching the walls of the artery thinner, thereby compromising the artery wall's ability to stretch any further. At this point, the aneurysm is at risk of rupturing and causing potentially fatal bleeding, just as a balloon will pop when blown up too much.

UCSF vascular surgeons have over 50 years of experience in complex abdominal aortic aneurysm repair, having pioneered many of the endovascular procedures for treating aneurysms that are in use today.

UCSF Medical Center earned a “high performance” rating – the highest rating possible – for abdominal aortic aneurysm repair in the U.S. News & World Report Best Hospitals survey for the second year in a row. The survey evaluated data from more than 4,500 hospitals.

Location and Classification

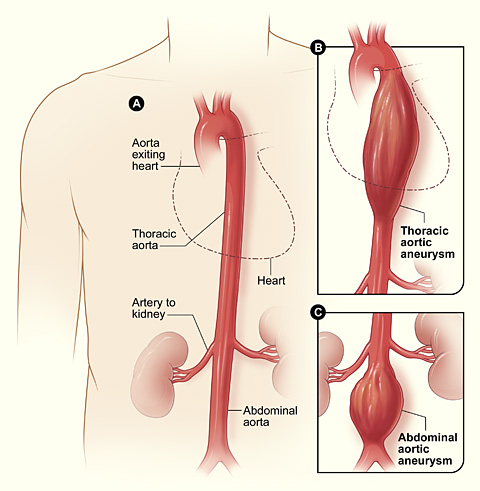

Aneurysms can occur anywhere along or in the immediate vicinity of the aorta. They are classified into several groups according to their location:

- Abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs) - Most aortic aneurysms (AAs) occur in the abdominal aorta. These are called abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs). Although most abdominal aortic aneurysms are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis, the most common complication remains life-threatening rupture with hemorrhage.

- Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm (TAA) These occur in the thoracic aorta, the upper part of the aorta and are also subject to rupture.

- TAAs are further subdivided subdivided into the following three groups:

-

Ascending aortic aneurysms

-

Aortic arch aneurysms (arteries that branch off the top of the aorta and form an arch)

-

Descending thoracic aneurysms, also called thoracoabdominal aneurysms (see below)

-

- Thoracoabdominal aneurysms (TAAAs) - Aneurysms that coexist in both segments of the aorta (thoracic and abdominal) are termed thoracoabdominal aneurysms (TAAAs).

-

Visceral Artery Aneurysms

Aneurysms can also occur in the branches coming off the aorta which supply blood to the vital organs, such as the liver, spleen, kidneys and intestines. This type of aneurysm is classified as a visceral (organ) artery aneurysm.

Aortic Aneurysms

Figure A shows a normal aorta. Figure B shows a thoracic aortic aneurysm (which is located behind the heart). Figure C shows an abdominal aortic aneurysm located below the arteries that supply blood to the kidneys.

Risk Factors

There are several risk factors for the development of aortic aneurysms including:

- Atherosclerosis ("hardening of the arteries")

- Hypertension (high blood pressure) causes increased pressure on the weakened portion of the aorta leading to stretching and bulging of the artery wall over time and the development of an aneurysm.

- Infection or inflammation

- Smoking (greater than 100 cigarettes in a lifetime)

- Age greater than 65 years old

- Male gender (Men are approximately 6 times more likely to get an abdominal aortic aneurysm than women)

- Inherited connective tissue disorders (Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, collagen vascular diseases) are genetic defects in collagen, which is one of the main building blocks of artery walls, including the aorta

- COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease)

- Patients with a 1st degree relative with an abdominal aortic aneurysm have a greater risk of developing an aneurysm themselves.

Signs and Symptoms

Unfortunately, most aortic aneurysms are asymptomatic. That is, they do not cause any symptoms until the aneurysm ruptures. However, many aneurysms are discovered by accident while a patient is being evaluated with a CT scan (computerized tomography) or MRI scan (magnetic resonance imaging) for another medical problem.

An abdominal aortic aneurysm that is rapidly expanding may cause abdominal, flank, or chest pain. On rare occasions, a pulsatile mass may be felt in the abdomen when there is an abdominal aortic aneurysm. Popliteal aneurysms may result in calf discomfort, claudication (discomfort with walking) or a pulsatile mass felt behind the knee.

Diagnosis

Most arterial aneurysms are discovered accidentally. Abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA) can be detected using a CT scan or MRI scan as well. Additionally, a large AAA may cast a shadow on a plain abdominal x-ray similar to that of a thoracic aortic aneurysm during a chest x-ray. However, both types of plain x-rays are not reliable in detecting aneurysms due to the many organs and other structures that are in the same vicinity as the aneurysms.

An abdominal US (ultrasound) is an excellent, non-invasive test that can be used to detect (screen) for abdominal aortic aneurysms and estimate the overall size of the aneurysm. Unfortunately, ultrasound (US) does not work well for screening of thoracic aortic aneurysms because of the large chest cavity.

A CT or MRI scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis, when performed with the addition of contrast dye, further enhances the characteristics of aneurysms and provides greater detail for the vascular surgeon to monitor the growth of the aneurysm and/or make plans for surgical repair of the aneurysm. When a CT or MRI scan is ordered with contrast dye, to evaluate the blood vessels (aorta, arteries and veins), the test is either called a CTA (computerized tomographic angiogram) or MRA (magnetic resonance angiogram), which results in finer cuts (slices) of images to better visualize the fine details of the blood vessels' anatomy.

On rare occasions a vascular surgeon may find it necessary to perform a procedure known as aortography, also known as an aortogram, to evaluate the aorta, the aneurysm, and how the aneurysm affects the branches of blood vessels coming off of the aorta. First, the groin is injected with a local anesthetic which numbs the area, then a catheter is placed into an artery in the groin and directed into the aorta. Contrast dye is injected into the aorta, aneurysm, and blood vessels branching off of the aorta, which provides the vascular surgeon with a detailed picture of the blood flow in these areas.

At the same time, contrast dye can be injected into the lower extremities, if deemed necessary, to evaluate the blood flow into the legs and any aneurysm(s), and how the aneurysm(s) affects the blood flowing into the feet.

Treatment

Watchful Waiting Period

Most arterial aneurysms require "watchful waiting" as the initial treatment of choice if they are discovered early and are still small. During this time period, the aneurysm is not considered large enough to warrant undergoing surgery to repair it, since the benefit of fixing the aneurysm at a smaller size does not outweigh the risks and complications of the surgery itself.

During the "watchful waiting" period, the vascular surgeon will monitor the growth of the aneurysm every 6 to 12 months by obtaining serial CT or MRI scans or ultrasounds. Once the aneurysm grows to a significant size and is at risk of rupturing, the benefits of repairing the aneurysm become greater than the risks and complications of surgery, or of not fixing the aneurysm altogether.

Once the aneurysm has reached a size which places it at risk for rupture, then surgical options are considered depending on several factors:

- Patient's age, past medical and surgical history, current health status

- Aneurysm type, location, & size

- Anatomy of aorta & arteries branching off of aorta to visceral organs and legs

Vascular surgeons at UCSF Medical Center perform both conventional open surgical repair, as well as minimally invasive endovascular repair for aneurysmal disease. The type of procedure performed is determined by the patient's medical status and the characteristics of the aneurysm.

Conventional Open Procedure

The conventional open surgical repair of aneurysms involves opening the abdominal cavity in the case of an abdominal aortic aneurysm, and sewing a synthetic graft inside the aneurysm to the artery above and below it to prevent the aneurysm from rupturing. In essence, relining the weakened aorta with a sleeve of material making the aorta stronger.

Endovascular Repair

A newer approach, called an endovascular repair, involves the use of a catheter that is inserted into the groin, in a similar fashion as an aortogram; however, the catheter is used to insert a self-expanding stent graft into the aneurysm. Endovascular repair of aneurysms does not require a large incision and has a substantially shorter recovery than the conventional open surgical approach. Not all aneurysms are suitable for endovascular repair; however, vascular surgeons at UCSF Medical Center are experts in the treatment of aneurysms using the conventional and endovascular approach.

UCSF vascular surgeons have extensive experience performing surgery for complex aortic aneurysms - those that involve the arteries to the kidneys or intestines - and is recognized as having one of the lowest mortality rates reported to date. Similarly, our vascular surgeons pioneered endovascular repair of aneurysms, particularly those involving the aorta in the upper abdomen where blood vessels branch off to the vital organs arise and in the chest. Our surgeons are also principal investigators in clinical trials of new endovascular devices to treat aneurysms.